Saturday

Oct072006

Waterfront At Night

Saturday, October 7, 2006 at 03:44AM

Saturday, October 7, 2006 at 03:44AM

The photo above was taken around 10:15 pm, under the light of a nearly-full moon. I parked the camera on a tripod and left the shutter open for 30 seconds. Unlike a human eye, a camera can “store” light (either on film granules or light-sensitive receptors found in digital cameras), transforming low levels of light into much higher levels. All of the light in this photo is from the moon. (Well, technically the light is from the sun. The moon is only acting as a reflector.)

Since the camera was kept still (being perched on a tripod), motion during the time of exposure - otherwise known as "blurring" - was kept to a minimum. You CAN see some blurring in the photo by looking at the surface of the water or the nearest blob. There was a slight breeze on this night and the water and blob certainly moved over the span of 30 seconds.

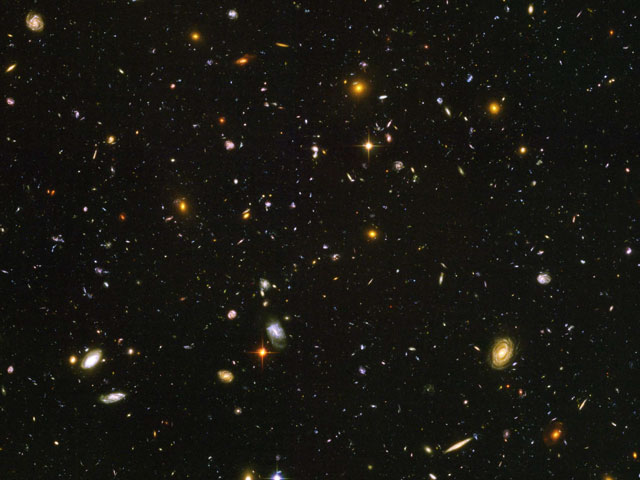

Obviously, this photo looks very different than what would be seen with the eyes. As I mentioned, the human eye cannot “store” light. Light excites the photo-receptors in the eye (”rods” and “cones”), a nervous signal is produced, and the amount of light is perceived by the brain. What light is present at any given singular moment in time is all that will be perceived. In this respect, a camera (or other similar device, such as a CCD imager) beats the human eye. A well-known instance of this “light storing” capability being exploited is in astronomic photographs. Most of objects in space that are photographed are much too faint to be seen by human eyes, particularly in any detail. Our eyes just can’t “hold” enough of the faint light. A camera, however, can store the light - even if very faint - and bring the invisible to light (so to speak). My favorite example of this is a photograph called the “Hubble Ultra Deep Field”, a photograph created by pointing a very sensitive camera towards exactly the same spot in deep space over a long period of time. The resulting photo reveals light captured over 3 months time…talk about storing light! Almost everything visible in the HUDF photo is a distant galaxy, with the exception of a few “nearby” stars. These galaxies are so far away and so faint that it would be impossible for the human eye to detect them. However, by storing the miniscule amounts of light reaching Earth for over three months, the Hubble Telescope was able to resolve these objects. Furthermore, since these galaxies are so far away - some possibly billions of light years away - this photo is not only a look across huge distances, but also across huge spans of time. These galaxies appear to us as they looked millions, and possibly billions, of years ago.

However, let’s not despair. The human eye, despite it’s light-storing inadequancy, beats the pants off any camera in most other respects. For one thing, no camera (that I’m aware of) can handle contrast like the human eye. Here’s what I mean: Take a look at the two photos below. For a camera, these photos present an almost impossible challenge - properly exposing both dark (inside the gym) and bright (outside the gym) areas. It is possible that there are specialized cameras capable of doing this (probably by utilizing separately metered areas of exposure), but for the most part cameras just can’t handle this kind of contrast (very bright brights and very dark darks). In one photo, the inside of the gym is (almost) correctly exposed, but the outside is horribly over-exposed. In the other photo the situation is reversed: the outside is correctly exposed but the inside of the gym is very much under-exposed.

The human eye, however, can handle this type of contrast easily. When shooting photographs, any decent photographer will try to minimize extreme contrasts. Shadows across an otherwise brightly lit face, for example, almost always turn out bad for a photographer. The camera just can’t handle the contrast between light and dark. For our eye, though, we hardly even notice. Our eyes can simultaneously adjust for a multitude of contrasts. We would have no problem looking across this gym and seeing the basketball players AND the kids outside in flawless exposure.

The other way in which our eyes triumph over the “eyes” of a camera is obvious. We never stop seeing. As long as our eyes are open, they are receiving and processing all that is around us. Our eyes are capable of processing a continuous and never-ending stream of information: light intensity, color, contrast, motion, shading…our eyes never miss a beat (assuming they are healthy). A camera, on the other hand, only captures light from a single, narrowly defined space, and only over a short span of time. It really wouldn’t do to substitue our eyes for cameras, despite their great ability to store light!

I truly appreciate good photography. I am amazed by the technology of cameras which allows them to capture and manipulate and store light in a way that no human eye can approach. I am furthermore thankful for the fact that this feature of cameras can reveal to us the beauty, splendor and wonder of the heavens, of deep space. When viewing a photograph which displays the subtleties and nuances and hidden gems of deep space, I am almost always filled with a deep sense of the miraculous, of the Numinous, of God Himself. But I am also mindful that the real miracle lies within my own body, my eyes. What they can do and how they do it…how they link directly to the brain and allow me to not only see the world around me, in all its color and contrast and intensity, but to interpret what is around me…this is the true wonder of imaging. And it isn’t lost on me that I can use these two miracles of creation, my eyes, to observe the equally grand miracle of deep space, made possible by a smaller “miracle” of technology, a camera.

Daver |

Daver |  Post a Comment |

Post a Comment | in  Whatnot

Whatnot

Whatnot

Whatnot

Reader Comments